THE HAMMER PARTY

LOS PICOLETOS + ADRIÁN CASTAÑEDA

From 28th November to 23rd December.

Now my hammer rages cruelly against its prison. Pieces of stone fly out of the stone: what do I care? In the twilight of his life, Friedrich Nietzsche maximises his intellectual and literary belligerence, presenting us with his philosophy of the hammer in various texts, which translates into a forceful criticism of Western philosophy, morality and religion. This critique, whose main objective is the destruction and subsequent reconstruction of a value - transvaluation, as the German would say - implies a break with all dogmatic and harmful theories that (self-)enslave human beings. In this same line of public denunciation is The Hammer Party, an exhibition proposal that brings together the work of Adrián Castañeda (Salamanca, Spain, 1990) and Los Picoletos (Dante Litvak, Buenos Aires, Argentina, 1990, and Fabro Tranchida, Buenos Aires, Argentina, 1987).

The artists focus their discourse on the difficulties of migratory flows in European territory and on the institutional violence exercised on migrants that time and again - physically and intangibly - violate many of the articles of universal human rights, all of them ratified in Paris by the General Assembly of the United Nations (resolution 217 A-III of 10 December 1948), just three years after the end of the Second World War. In this sense, The Hammer Party presents two different points of view of a vulnerability of citizens' rights such as the processes of regularisation of migrants: on the one hand, that of the observer who carries out a self-critical task in which he analyses and questions his own privileges (Adrián Castañeda) and from the experience of those who know first-hand the bureaucratic obstacles of the public administration (Los Picoletos). In both cases, the question is the same: what does it mean to be regularised? Based on data from 2021, more than 23 million people are migrants within the European Union, which corresponds to 5.1% of the total population.

By considering migrants as a minority group - despite the fact that we are talking about millions of people - European - and non-European - social policies are diluted, causing migratory flows to be assimilated as a non-priority issue, even though the media portrays the opposite. By not having a real preference among political concerns, the coordination and execution of administrations at both national and international level lose in efficiency and, above all, in humanity. This lack of humanity is fully portrayed at borders, as clear discriminatory elements where the concept of justice disappears. The term citizenship is also present at borders, a term that over the years has acquired a theoretical broadening, especially in Europe, propitiated by the maximisation of its multicultural component, by the resurgence of nationalist movements, by the rise of the extreme right, by the generalised fear of the loss of the welfare state - exacerbated after the economic crises of 2008 and 2020 - and by the generalised fear of the loss of the welfare state - exacerbated after the economic crises of 2008 and 2020 - and by the generalised fear of the loss of the welfare state.

Economic crises of 2008 and 2020 - and, of course, by the phenomenon of mass migration. But again, a question arises: what does it mean to have citizenship? The word itself is linked to a specific geopolitical space and thus becomes exclusionary. If there is exclusion, there is discrimination and inequality; a discrimination and inequality, by the way, that is fully legitimised, which further aggravates the situation.

Citizenship - which is nothing more than a piece of paper - endows the individual with socio-political and economic value, and thus gives him or her a social and institutional affection that the so-called non-citizen does not enjoy. This is made clear by our artists. On the one hand, Adrián Castañeda focuses his discourse on the situation of Unaccompanied Foreign Minors (MENAs) and on the real reception mechanisms for these young people in destination countries. According to the Attorney General's Office, almost 3,000 unaccompanied minors arrived in Spain in 2019. These children, most of them adolescents, as soon as they are detained, receive the first institutional violence: they are treated as if they were criminals.

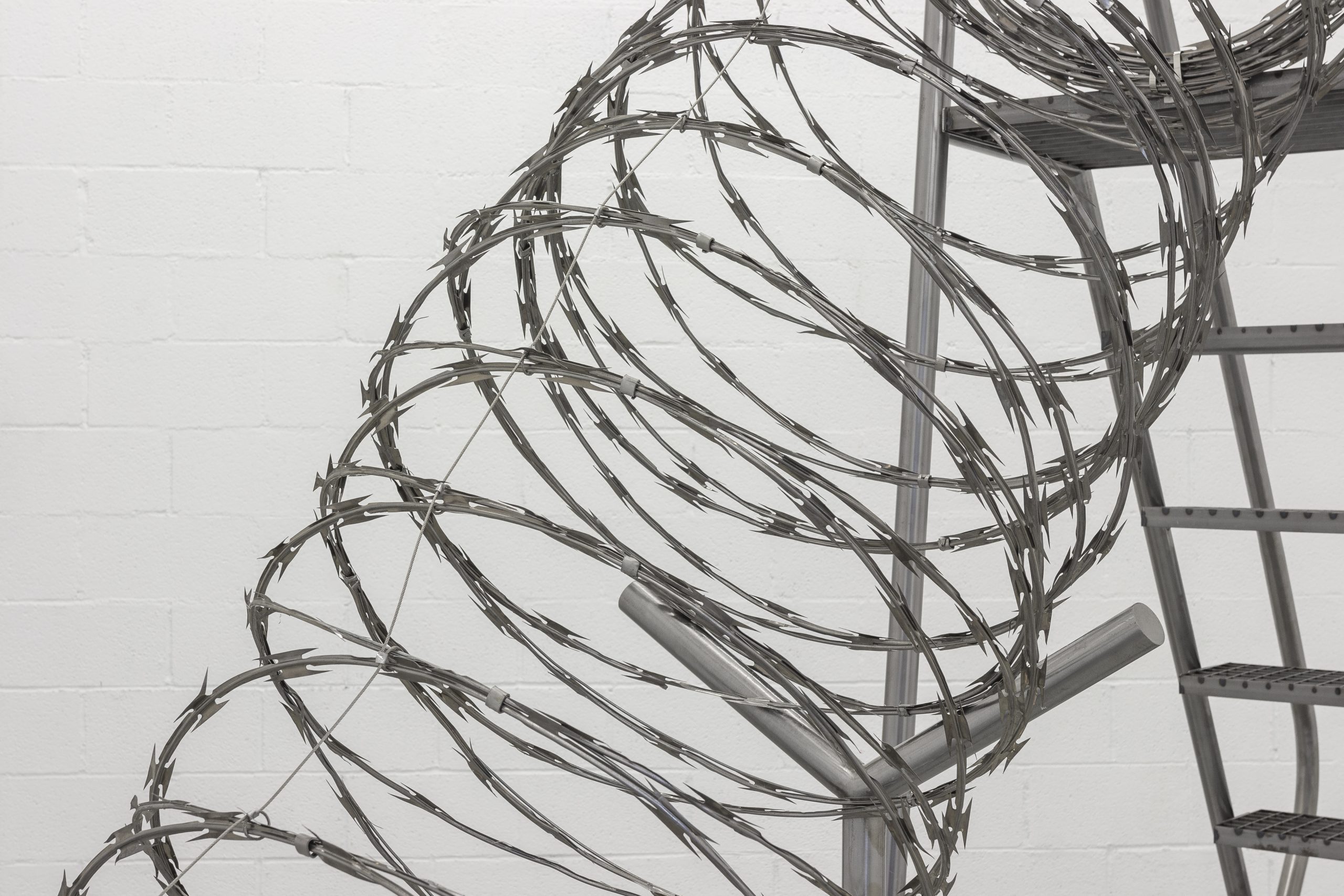

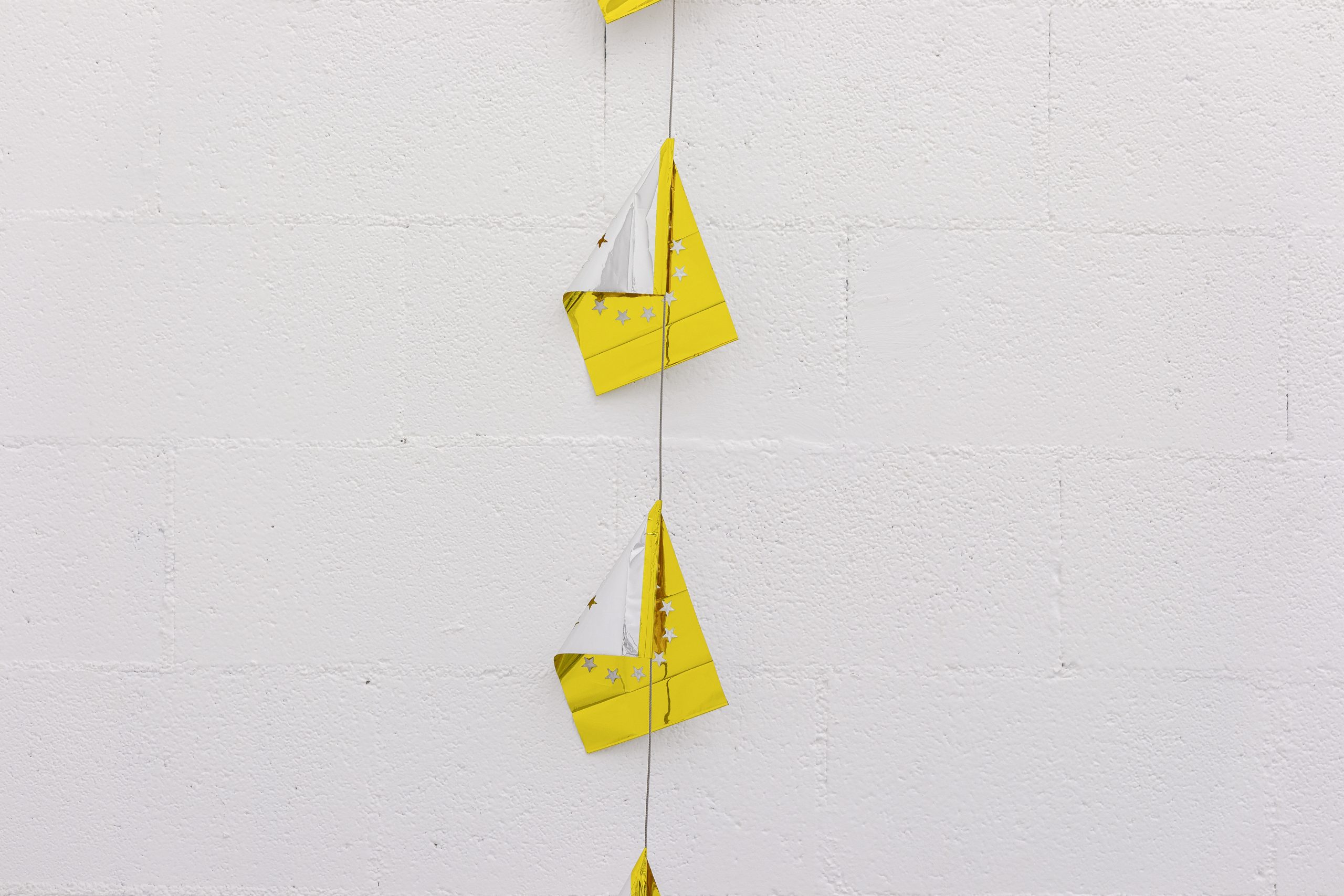

In other words, they are taken to a police station, fingerprinted, photographed and made to wait in a dungeon-like facility. Faced with this scenario, Castañeda questions the real need for this (mis)treatment and the harsh message behind this system, flooded with repression, control and hegemony. As we are accustomed to, the work of the artist from Salamanca revolves around the representation of power - from the physical to the symbolic - in contemporary society and the need for the implementation of a model of society in which citizens participate directly and almost without intermediaries in decision-making. All this is visibly embodied in the central piece of his composition: a slide made from a coil of concertina wire Through a device that is clearly related to childhood, Castañeda makes a forceful assault on the audience, forcing them to reflect, among other things, on children's rights. On the other hand, Los Picoletos takes as its starting point the situation of a series of young migrants who work in food delivery service platforms, as is the case with companies such as Glovo or Just Eat, among others. In 2019, the Fundamental Rights Agency (FRA) of the European Union published a report that collected the testimony of 327 migrants, where the level of violence, exploitation and abuse to which they are subjected was palpable. But after so much despotism, where are the migrants' personal and work-related dreams and ambitions? The artists produced a whole series of wax votive offerings2 of young migrants who work in these food delivery service apps, representing not only parts of their bodies but also including a whole series of objects linked to the desires of these people. Los Picoletos have placed the votive offerings inside scales, an instrument that not only serves to measure their mass, but also allows them to demonstrate the perverse relationship that currently exists between desire, precarious work, youth and frustration.

The global financial crisis and the economic slowdown have engendered the highest number of unemployed young people in history, multiply the digit if we are talking about young migrants, for whom the lack of decent employment represents the main obstacle to their progress as individuals.

It is, to say the least, admirable to find exhibitions where artists talk to and from their own generation, trying to give a voice to those who don't have one and, in passing, talk about themselves and their worries, fears and failures. An exhibition where irony tries to mislead us -as spectators and as citizens-, to confuse us in an atmosphere where pain and impotence are the real protagonists. Welcome to The Hammer Party, welcome to the party of the worker, to the party of frustration and precariousness: welcome to the party of decadence. Welcome to the party of the wire slide and the thermal blanket pennants; to the party of the ritual of the and thermal blanket banners; to the party of popular ritual and labour exploitation.

Adonay Bermudez

-

Del 28 de Noviembre al 23 de Diciembre.

Ahora mi martillo se enfurece cruelmente contra su prisión. De la piedra saltan pedazos: ¿qué me importa?. Ya en el ocaso de su vida Friedrich Nietzsche maximiza su beligerancia intelectual y literaria, presentándonos en diversos textos y a ralentí su filosofía del martillo, que se traduce en una contundente crítica hacia la filosofía occidental, la moral o la religión. Dicha crítica, cuyo objetivo principal es la destrucción y posterior reconstrucción de un valor –la transvaloración, que diría el alemán-, supone una ruptura con todas las teorías dogmáticas y nocivas que (auto)esclavizan al ser humano. En esta misma línea de denuncia pública se localiza The Hammer Party, una propuesta expositiva que aúna el trabajo de Adrián Castañeda (Salamanca, España, 1990) y Los Picoletos (Dante Litvak, Buenos Aires, Argentina, 1990, y Fabro Tranchida, Buenos Aires, Argentina, 1987).

Los artistas centran su discurso en las dificultades de los flujos migratorios en el territorio europeo y en las violencias institucionales ejercidas sobre los migrantes que atropellan una y otra vez –de manera física e intangible- muchos de los artículos de los derechos humanos universales; todos ellos ratificados en París por la Asamblea General de la Organización de las Nacionales Unidas (resolución 217 A-III del 10 de diciembre de 1948), justo tres años después de que acabase la II Guerra Mundial. En este sentido, The Hammer Party presenta dos ópticas diferentes de una vulnerabilidad de los derechos ciudadanos como son los procesos de regularización de los migrantes: por un lado, la del observador que realiza una labor de autocrítica donde se analiza y cuestiona sus propios privilegios (Adrián Castañeda) y desde la experiencia que conoce de primera mano las trabas burocráticas de la administración pública (Los Picoletos). En ambos casos la pregunta es la misma: ¿qué significa estar regularizado?. Partiendo de unos datos de 2021, más de 23 millones de personas son migrantes dentro de la Unión Europea, lo que corresponde al 5,1% del total de la población. Al considerar a los migrantes como grupo minoritario –pese a que hablamos de millones de personas- las políticas sociales europeas –y las no europeas- se diluyen, provocando que los flujos migratorios se asimilen como un asunto no prioritario, aunque mediáticamente se nos plantee justo lo opuesto. Al no contar con una preferencia real dentro de las preocupaciones políticas, la coordinación y ejecución de las administraciones tanto a nivel nacional como internacional pierden en eficacia y, sobre todo, en humanidad.

Esta falta de humanidad queda plenamente retratada en las fronteras, como claros elementos discriminatorios donde el concepto de justicia desaparece. También con la frontera hace acto de presencia el término de ciudadanía, un término que con los años ha ido adquiriendo un ensanche teórico, especialmente en Europa, propiciado por la maximización de su componente multicultural, por el resurgimiento de los movimientos nacionalistas, por el auge de la extrema derecha, por el miedo generalizado a la pérdida del estado de bienestar –agudizado tras las crisis

económicas de 2008 y 2020- y, por supuesto, por el fenómeno de las migraciones masivas. Pero, nuevamente, aparece una pregunta: ¿qué significa tener la ciudadanía? La propia palabra está vinculada a un espacio geopolítico concreto y, por tanto, se convierte en excluyente. Si hay exclusión, hay discriminación y desigualdad; una discriminación y desigualdad, por cierto, totalmente legitimada, lo que agrava aún más la situación. La ciudadanía –que no deja de ser un papel- dota de valor sociopolítico y económico al individuo y, por ende, le supone un afecto social e institucional del que no goza el denominado no ciudadano. Así lo dejan patente nuestros artistas. Por una parte, Adrián Castañeda fija su discurso en la situación de los Menores Extranjeros No Acompañados (MENAs) y en los verdaderos mecanismos de acogida para estos jóvenes en los países de destino. Según la Fiscalía General del Estado, en 2019 llegaron a España casi 3.000 menores no acompañados. Estos niños, en su mayoría adolescentes, nada más ser detenidos reciben la primera violencia institucional: son tratados como se procede con

un criminal, es decir, se les traslada a una comisaría, se les toman las huellas, se les fotografía y se les hace esperar en dependencias similares a las de un calabozo. Ante este escenario, Castañeda cuestiona la necesidad real de este (mal)trato y del duro mensaje que hay detrás de este sistema, inundado de represión, control y hegemonía. Tal y como nos tiene acostumbrados, el trabajo del artista salmantino pivota en torno a la representación del poder -del físico al simbólico- en la sociedad contemporánea y a la necesidad de la implantación de un modelo de sociedad donde los ciudadanos participan de manera directa y casi sin intermediarios en la toma de decisiones. Todo ello queda visiblemente encarnado en la pieza central de su composición: un tobogán realizado con una bobina de alambre de concertina. A través de un dispositivo claramente relacionado con la niñez, Castañeda asesta con contundencia al público, obligándole a reflexionar, entre otras cosas, sobre los derechos de la infancia. Por otra parte, Los Picoletos tienen como punto de partida la situación de una serie de jóvenes migrantes que trabajan en plataformas de servicio de reparto de comida, como es el caso de empresas como Glovo o Just Eat, entre otras. En 2019, la Agencia de Derechos Fundamentales (FRA) de la Unión Europea publicó un informe que recogía el testimonio de 327 migrantes, donde quedaba palpable el nivel de violencia, explotación y abuso al que están sometidos. Pero, después de tanto despotismo, ¿dónde quedan los sueños y las ambiciones personales y laborales de los migrantes? Los artistas llevan a cabo toda una serie de exvotos de cera2 de jóvenes migrantes que trabajan en dichas apps de servicio de reparto de comida, representando no solo partes de los cuerpos sino incluyendo toda una serie de objetos vinculados a los deseos de dichas personas. Eso sí, Los Picoletos han situado los exvotos dentro de balanzas, instrumento que no solo sirve para medir la masa de los mismos, sino que les permite demostrar la relación tan perversa que actualmente existe entre deseo, trabajo precarizado, juventud y frustración. La crisis financiera global y la desaceleración económica han engendrado el mayor número de desempleados jóvenes de la historia, multipliquemos el dígito si hablamos de jóvenes migrantes, para quienes la falta de empleo digno representa el principal obstáculo a su progreso como individuos.

Es, como mínimo, admirable encontrar exposiciones donde los artistas hablen con y desde su propia generación, intentando dar voz a los que no la tienen y, de paso, hablar de ellos mismos y de sus preocupaciones, miedos y fracasos. Una muestra donde la ironía intenta despistarnos –como espectadores y como ciudadanos-, de confundirnos en una atmósfera donde el dolor y la impotencia son los verdaderos protagonistas. Bienvenido a The Hammer Party, bienvenido a la fiesta del obrero, a la fiesta de la frustración y de la precariedad: bienvenido a la fiesta de la decadencia. Bienvenido a la fiesta del tobogán de alambre y de los banderines de mantas

térmicas; a la fiesta del ritual popular y de la explotación laboral.

Adonay Bermúdez